Is It True?: The Affair of the Key

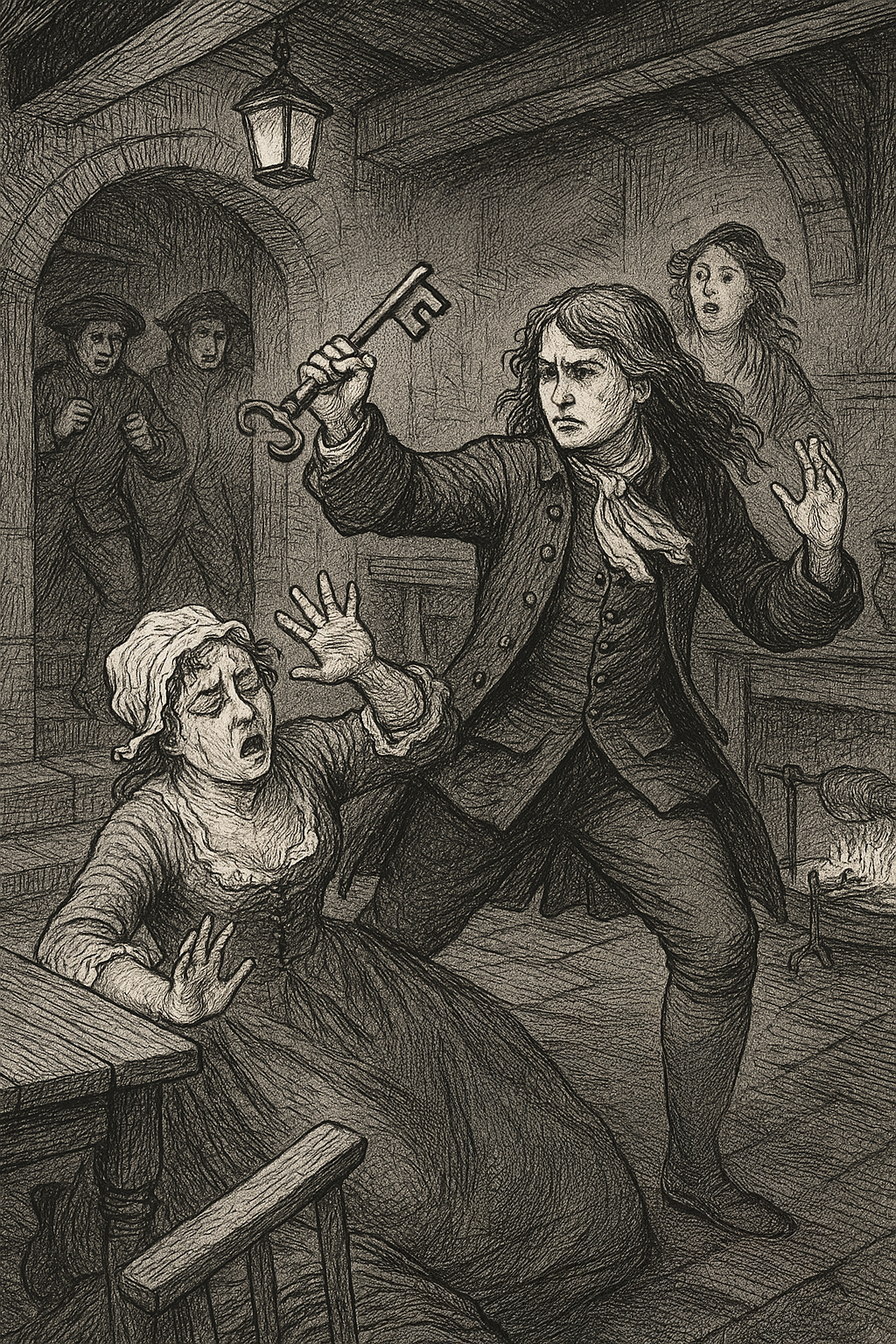

“The Affair of the Key” (AI sketch)

It can be hard to tell which stories about La Maupin are true and which are myths that grew up around her. As a result, I often find myself playing the role of textual critic, trying to evaluate what is plausible, what sounds real, and what is made up. Did she really fight three men at the same time? Did it happen more than once? Did she burn down a convent? Do I really believe this story or that? Does a given account fit into the narrative of her life that I am trying to tell? Is it the sort of thing that someone is likely to have made up?

This story is one that feels very real to me. It does so in part because it has lots of nice detail, and in part because it has a couple of inconsistencies and lingering questions, and real life is like that. In the end, though, it’s simply too good to leave out, and it helps me build a picture of Julie d’Aubigné as a complex character, part hero, part villain. It fleshes her out, and makes her feel real.

The basic story

According to our best sources, at about 9:00 in the evening of the 6th of September, 1700, La Maupin got into a heated argument with her landlord M. Langlois and his servant, Marguerite Fouré. Langlois retreated and La Maupin attacked Fouré with a large key. The ruckus drew a crowd of neighbors, and the police were called. Commissaire Jean Regnault investigated and reported the presence of La Maupin, her “sister” and two (or three) lackeys. The next day, depositions were taken from several of the neighbors. So far as we can tell, La Maupin was never charged or punished.

What this tells us

The naming of an actual police commissaire, Jean Regnault, the quoting of his reports and witness statements, and the fact that the ID number given for the reports does, in fact, correspond to the file of Commissaire Regnault in the French National Archive all add a level of detail that bespeaks an actual incident. The reports also provide the names of the landlord, the cook, and several neighbors and witnesses, which help fill out the context, and situate our heroine in a specific neighborhood.

Interestingly, it also speaks of a sister and two or three lackeys, unmentioned by any prior source. The only relatives ever spoken of in any other source are La Maupin's father and husband. This is the only appearance of a sister. A possible explanation is that rather than being her actual sister, the woman is someone who lives with, or is a frequent vistor of, Julie's whom she passes off as her sister in order to control gossip. This is how I am treating her.

Then there is the matter of the “lackeys”. The French here is “laquais”, generally translated as “lackeys” or “footmen”. Either way, they are commoner servants (footmen or manservants) who dress in the livery of the person they serve. Regnault says that the cook wanted to lodge a complaint “against one named Maupin, singer at the Opera, her sister, and three lackeys of unknown identity”. In her complaint, the cook says that at one point La Maupin “threw herself upon the complainant, aided by her sister and two lackeys”. One of the witnesses testifies to seeing “several people—men, women, and lackeys, some dressed in red and gray”.

It would thus seem that we have objective evidence that Mlle. Maupin, who sang with the Opéra in the fall of 1700, lived just a couple of blocks from the Opéra and maintained a household with at least two liveried servants and a female companion that she called her sister. She did not own the home, but rather rented rooms from one M. Langlois, who employed a cook and, in certain circumstances, provided meals. In at least one incident she, perhaps with the aid of her lackeys, assaulted people she knew. This doesn’t prove that all of the wild stories told about La Maupin are true, but it helps us to build a fact-based picture of the scandalous La Maupin.

As presented by Fradin

Perhaps the best source for the incident is in Gabriel Letainturier-Fradin’s 1904 book (available from Archive.org), La Maupin (1670–1707), Sa Vie, Ses Duels, Ses Aventures. While presented as a novel, Fradin does what he can to accurately portray La Maupin’s life and cites his sources. When he takes creative license, he lets us know. He certainly passes on sheer myth, and does add his own material, but I have yet to find him fictionalizing a source. In this case, he presents material he has taken from specific documents in the National Archives in Paris, citing their specific collection, series and item number. I have not yet been able to locate actual copies of those documents, but I have been able to verify that the reference number (Y 15561) that he provides does, in fact, correspond to the reports of Commissaire Jean Regnault for the year 1700. For now, I am regarding this as factual.

Here is his account, including the quotations from the reports of Regnault and a surgeon named Desportes who examined the cook, Marguerite Fouré. It is an OCR transcript of a scan of Fradin’s book (available from Archive.org), cleaned up (to the left) and translated to English (to the right) by ChatGPT 4o.

Original French

Cette rue [Rue Saint-Honoré] et les rues adjacentes, à côté des hôtels princiers, avaient, en bordure, des maisons de belle apparence protégées contre le heurt des voitures et des lourds carrosses par des bornes en saillie.

La Maupin occupait, dans une de ces dernières maisons, un magnifique appartement qu'elle louait au sieur Langlois, rue Traversière-Saint-Honoré. Les différends des locataires avec leurs propriétaires ne datent pas d'aujourd'hui; déjà à cette époque de fréquentes querelles s'élevaient entre les uns et les autres, et, si La Maupin, avec son caractère violent, son esprit batailleur, devait se faire respecter l'épée à la main, elle n'ignorait pas non plus l'art de se défendre ou d'attaquer avec les poings, lorsqu'un bourgeois ou une servante affrontait sa colère.

Une affaire de ce genre lui valut une forte semonce du commissaire Jean Regnault, et, n'eût été sa situation et sa réputation d'actrice de l'Académie Royale de Musique, elle n'en serait pas sortie à si bon compte.

Après la représentation, vers les neuf heures du soir, le 6 septembre 1700, La Maupin était rentrée chez elle comme d'habitude ; puis, elle descendit dans la cuisine pour demander à souper. Le propriétaire répondit qu'il n'avait pas à lui donner à manger, leur contrat ne contenant plus cette clause. Emportée, et peut-être affamée, la chanteuse saisit une éclanche de mouton que la servante tirait à ce moment de la broche. Brandissant cette massue d'un nouveau genre, elle la lança violemment sur la figure du sieur Langlois ; heureusement, il se retira à temps, et la viande alla s'aplatir sur la porte de la salle. La servante agitait sa broche ; des laquais de La Maupin vinrent se mêler à la discussion, la cohue devint bientôt générale. Démunie de son projectile, la comédienne s'arma d'une grosse clef et en porta un terrible coup à la cuisinière. Le bruit de la bataille attira les voisins, qui s'empressèrent d'avertir le commissaire. L'arrivée de ce magistrat mit fin au combat. Après avoir informé, il dressa le procès-verbal suivant :

L'an 1700, le 6 septembre, neuf heures et demie du soir, nous, Jean Regnault, etc., sommes transporté rue Traversière, en la maison tenue et occupée par le sieur Langlois, bourgeois de Paris, où étant entré dans une cuisine, à droite en entrant sous la grande porte dans icelle nous avons trouvé Marguerite Fouré, servante du dit Langlois, blessée et saignant de la tête au-dessus de l'œil droit, ses coiffures de toile blanche garnies de dentelles déchirées en morceaux, son habit d'étoffe grise marqué de sang en plusieurs endroits par devant; laquelle en cet état nous a rendu plainte à l'encontre de la nommée Maupin, chanteuse à l'Opéra, sa sœur(1), et à I'encontre de trois quidams laquais; et dit que la dite Maupin étant descendue de sa chambre dans ladite cuisine, demandant à souper, le sieur Langlois, son maître, lui aurait fait entendre qu'il n'était plus obligé de lui donner à manger, le marché fait entre eux ayant cessé ; la dite Maupin, violente et emportée de colère, auroit pris une éclanche de mouton que la plaignante tiroit de la broche, et vouloit en frapper le dit sieur Langlois ; le dit sieur Langlois s'étant retiré, le coup de la dite éclanche auroit donné contre la porte ; en reniant Dieu, auroit pris la grosse clef de la porte et de la dite clef en auroit donné un coup à la tête de la plaignante et icelle blessée à sang et plaie ouverte au-dessus de l'œil droit ; ensuite, s'est jetée sur elle, accompagnée de sa sœur et de ses deux laquais, l'auroit terrassée sur le pavé de la dite cuisine, à elle donné plusieurs coups de pied, coups de poing, déchiré ses coiffures et mise en l'état où nous la voyons ; sujet pour quoi elle nous rend la présente plainte(2).

Son rapport terminé, voyant les combattants un peu calmés, le commissaire se retira, prenant le nom des témoins de la scène pour les entendre le lendemain.

En effet, le jour suivant, 7 septembre 1700, dès neuf heures du matin, le magistrat entendit le premier témoin de l'affaire, le sieur René Mérot, tailleur, travaillant chez Rabier, maître-tailleur, rue Traversière, paroisse Saint-Roch.

Le comparant déposa en ces termes :

Le jour d'hier, environ les neuf heures du soir, ayant entendu du bruit de la maison du sieur Rabier, son maître, seroit sorti à la porte de la rue, auroit remarqué que le bruit estoit dans la maison attenant, tenue par le sieur Langlois et où est demeurante La Maupin et sa sœur; la sœur de laquelle Maupin était à la fenêtre du premier étage, parlant à une personne qui estoit de l'autre costé de la rue, aussi à une fenêtre, et à laquelle elle disoit:

«Ma sœur, parlant de la dite Maupin, avoit la grosse clef de la porte. »

Auroit appris dans le même instant que la dite Maupin avoit cassé la teste à la plaignante d'un coup de la grosse clef de la porte de la maison où elle est demeurante ; qui est tout ce qu'il a dit sçavoir.

Lecture à luy faite de sa dite déposition, a dit icelle contenir la vérité.

Après cette déclaration qui ne révélait rien de nouveau, le commissaire entendit la déposition du sieur Verand Raphaely, valet de chambre de la Marquise de Vances, qui demeurait près de l'immeuble occupé par La Maupin. Le laquais, fier de son rôle important dans cette affaire, déposa que :

Le jour d'hier, environ les neuf heures du soir, ayant entendu du bruit de la maison de la dame sa maîtresse, seroit sorti à la porte de la rue, auroit vu que le bruit étoit dans la maison attenante, occupée par le sieur Langlois; y étant entré, comme plusieurs autres, dans une cuisine qui est à droite en entrant sous la porte, auroit vu La Maupin, chanteuse à l'Opéra, couchée sur l'ais du plancher de la dite cuisine, se tenant aux cheveux avec la plaignante; ayant été séparées l'une et l'autre; relevée, la dite plaignante blessée et saignant audessus de l'œil droit; luy déposant, ayant ramassé deux morceaux de dentelle de la coiffure de la dite Maupin, les luy auroit rendu; quelques personnes ayant fait retirer la dite Maupin, la dite Maupin auroit fait plusieurs efforts pour y rentrer, de quoy elle auroit été empêchée; la plaignante ainsi blessée auroit dit que c'estoit d'un coup à elle donné par la dite Maupin avec la grosse clef de la porte cochère de la dite maison; qui est tout ce qu'il a dit sçavoir.

Lecture à luy faite de sa déposition, a dit icelle contenir la vérité et a signé : Raphaely.

Le troisième témoin interrogé fut Marie Soufflart, femme du maître-sellier Michel Bauchet, qui demeurait également près de là et était accourue au bruit de la querelle, accompagnée de sa fille, vers la maison de Langlois, et raconta ainsi ce qu'elle avait vu :

Le jour d'hier, environ neuf heures du soir, de la boutique ayant entendu du bruit dans la maison où est demeurante La Maupin, accusée, elle s'y est transportée avec sa fille; où étant entrées dans une cuisine à droite en entrant, avoit veu plusieurs personnes, hommes, femmes et laquais sans livrée, quelques-uns vestus de rouge et de gris, connus de vue pour estre d'une maison voisine, à travers lesquels avoit veu la plaignante, décoiffée, que l'on tenoit par les cheveux, sans avoir pu remarquer qui la tenoit, et se seroit ainsi retirée ; a depuis ouy dire que la dite plaignante avoit été blessée à la teste, qui est tout ce qu'elle a dit sçavoir.

Marie-Anne Bauchet, fille de la précédente :

Déposa que le jour d'hier, environ neuf heures du soir, étant dans la boutique de ses père et mère, ayant entendu du bruit dans la maison du sieur Langlois, elle s'y seroit transportée avec sa mère ; auroit veu, dans une cuisine en entrant à droite, la servante nommée Fourré, ainsi qu'elle n appris, décoiffée et que l'on maltraitoit de la main; n'a point remarqué qui la frappoit, mais avoit remarqué qu'elle avoit été terrassée sur le pavé de la cuisine, d'où elle avoit été relevée, et la dite déposante se seroit retirée un moment après avoir appris que la dite Fourré estoit blessée à la teste à sang et à playe ouverte ; qui est tout ce qu'elle a dit sçavoir.

Après ces dépositions anodines, il ne restait plus à connaître que la valeur et la force d'un coup donné par La Maupin; c'est ce que nous apprendra le chirurgien Desportes dans un rapport détaillé sur la blessure.

Je soussigné, chirurgien du Roy et maistre juré à Paris, certifie à tous ceux à qui il appartiendra, que le six septembre mil sept cent, entre neuf et dix heures du soir, j'ay esté a pelé pour voir et visiter, pancer et médicamenter, Marguerite Fouré, servante du sieur Langlois, demeurant rue Traversière en porte cochère. A laquelle j'auré trouvé une blessure au fron, partie de los coronal de grandeur d'un travers de doit, pénétrant jusqu'au péricrâne; plus, une contusion et murtrissure sur lavant bras, partie senestre; plus, nous avoir dit sentir plusieurs douleur en diferants endroitz de son corps ; sur laquelle blessure et contusion et murtrissure ma paru avoir esté faites par instrument contondant, tranchant comme chandelier, clef ou autre semblable ; et pour prévenir les suites dangereuses qui pouret san suivre, comme fieuvre et abcez, je lui ay prescrit un régime de vivre exat, de garder le lit, d'estre soignée et pansé et médicamente deux fois par jour et moienant de quoy la dite blessure poura estre guérie dans quinze jours sy accident narive; tout ce que dessus, je certifie véritable, en foy de quoi j'ay sine, fait à Paris le sept du présent mois et ans dessus.

Desportes(3).

Ce certificat, malgré l'absence d'orthographe qui le caractérise, témoigne du danger qu'il y avait à affronter la colère de Mademoiselle Maupin. Cette affaire n'eut pas de suites fâcheuses pour l'actrice, dont nous n'avons pas la défense; elle trouva sans doute à se disculper, ou bien on ferma les yeux et, comme on dit aujourd'hui, l'affaire fut classée.

(1) Par ce seul dossier nous avons appris que Mademoiselle Maupin avait une sœur ; personne n'en a jamais parlé dans les autres pièces que nous avons consultées. Etant donné les mœurs de la chanteuse, il se pourrait qu'elle ait fait passer pour sa parente une femme avec qui elle vivait.

(2) Archives Nationales. — Papiers des Commissaires y 15561. Dossier à la date du 6 sept. 1700.

(3) Archives Nationales. — Papiers des Commissaires y 15561.

English Translation (AI)

This street [Rue Saint-Honoré] and its neighboring ones, alongside princely mansions, were lined with fine-looking houses, protected from collision with vehicles and heavy coaches by projecting stone bollards.

La Maupin occupied a magnificent apartment in one of these last houses, which she rented from Sieur Langlois on Rue Traversière-Saint-Honoré. Disputes between tenants and landlords are nothing new; even at that time, frequent quarrels arose between them. And while La Maupin, with her fiery temperament and combative spirit, had to make herself respected with a sword in hand, she was also not ignorant of the art of defending or attacking with her fists when a bourgeois or a servant faced her wrath.

One such incident earned her a stern reprimand from Commissioner Jean Regnault. If not for her status and reputation as an actress at the Royal Academy of Music, she might not have escaped so easily.

On the evening of September 6, 1700, around nine o’clock, after a performance, La Maupin returned home as usual. She then went down to the kitchen to ask for supper. The landlord replied that he had nothing to give her to eat, as their contract no longer included that provision. Enraged, and perhaps hungry, the singer grabbed a shoulder of mutton that the servant was taking off the spit at that moment. Brandishing this improvised club, she hurled it violently at Sieur Langlois’s face. Fortunately, he stepped back in time, and the meat splattered against the dining room door. The servant, meanwhile, brandished her spit; La Maupin’s lackeys joined the fray, and soon the scuffle became general. Deprived of her projectile, the actress seized a large key and delivered a brutal blow to the cook. The noise of the fight attracted the neighbors, who quickly alerted the commissioner. His arrival put an end to the combat. After conducting his investigation, he drafted the following report:

“On the 6th of September, 1700, at half-past nine in the evening, we, Jean Regnault, etc., went to Rue Traversière, to the house owned and occupied by Sieur Langlois, a bourgeois of Paris. Upon entering the kitchen, to the right under the main entrance, we found Marguerite Fouré, servant to the said Langlois, injured and bleeding from a wound above her right eye, her white lace-trimmed headdress torn to pieces, her gray fabric dress stained with blood in several places. In this state, she lodged a complaint against one named Maupin, singer at the Opera, her ‘sister’(1), and against three lackeys of unknown identity. She stated that when Maupin came down from her room to the kitchen asking for supper, Sieur Langlois informed her that he was no longer obliged to provide her with food, as their agreement had ended. In a violent rage, the said Maupin grabbed a shoulder of mutton that the complainant was removing from the spit and attempted to strike Sieur Langlois with it. When he dodged, the meat hit the door. Cursing God, Maupin then took the large key to the door and struck the complainant on the head, causing an open wound above her right eye. She then threw herself upon the complainant, aided by her sister and two lackeys, knocked her to the ground, beat her with kicks and punches, tore her headdress, and left her in the state in which we found her. The complainant therefore submits this present complaint.”(2)

Having completed his report and seeing that the fighters had calmed down somewhat, the commissioner withdrew, taking the names of witnesses for questioning the following day.

On September 7, 1700, at nine in the morning, the magistrate heard the first witness, Sieur René Mérot, a tailor working for Master Tailor Rabier on Rue Traversière, parish of Saint-Roch.

Mérot testified as follows:

“The previous evening, around nine o’clock, hearing a commotion from my master’s house, I stepped outside and noticed that the noise was coming from the neighboring house, occupied by Sieur Langlois, where Maupin and her sister resided. I saw Maupin’s sister at the first-floor window, speaking to someone at another window across the street. She said:

‘My sister, speaking of Maupin, had the large door key.’ ”

At that moment, I also learned that the said Maupin had cracked the complainant’s head with a blow from the large key to the door of the house where she resided; that is all he said he knew.

Having had his deposition read to him, he stated that it contained the truth.

After this deposition, which revealed nothing new, the commissioner questioned Sieur Verand Raphaely, valet to the Marquise de Vances, who lived near La Maupin’s residence. Clearly enjoying his role in the matter, the valet declared:

“The previous evening, around nine o’clock, hearing noise from my mistress’s house, I stepped outside and saw that the commotion was in the neighboring house, occupied by Sieur Langlois. Entering, along with several others, into a kitchen to the right of the main entrance, I saw Maupin, singer at the Opera, sprawled on the kitchen floor, grappling with the complainant by the hair. They were separated; the complainant, once on her feet, was bleeding above the right eye. I picked up two torn pieces of lace from Maupin’s headdress and returned them to her. Some individuals forced Maupin to withdraw, though she made several attempts to re-enter. The injured complainant stated that Maupin had struck her with the large key to the carriage door of the house. That is all I know.”

Having had his deposition read to him, he stated that it contained the truth and signed: Raphaely.

The third witness was Marie Soufflart, wife of Master Saddler Michel Bauchet, who had rushed to the scene with her daughter upon hearing the noise. She recounted:

“The previous evening, around nine o’clock, I heard the disturbance in Maupin’s residence and went there with my daughter. Entering the kitchen, I saw several people—men, women, and lackeys, some dressed in red and gray, whom I recognized as from a neighboring house. Through them, I glimpsed the complainant, disheveled and being held by the hair, though I could not tell by whom. I later heard that she had been injured on the head. That is all I know.”

Marie-Anne Bauchet, her daughter, gave a similar statement.

She testified that on the previous day, around nine o’clock in the evening, while in her parents’ shop, she heard a commotion in Sieur Langlois’s house and went there with her mother. Upon entering the kitchen to the right, she saw the servant named Fourré—whom she later learned the name of—disheveled and being mistreated by hand. She did not see who was striking her but noticed that she had been knocked to the ground in the kitchen, from where she was then helped up. The witness withdrew shortly after learning that the said Fourré had suffered a head wound, with bleeding and an open wound. That is all she said she knew.

After these inconclusive testimonies, the only thing left was to determine the severity of Maupin’s blow. This was clarified by Surgeon Desportes in his detailed medical report:

“I, the undersigned, surgeon to the King and sworn master in Paris, certify to all whom it may concern that on September 6, 1700, between nine and ten in the evening, I was called to examine, treat, and medicate Marguerite Fouré, servant to Sieur Langlois, residing at Rue Traversière. I found a wound on her forehead, extending to the coronal bone, about a finger’s width across, penetrating to the periosteum. Additionally, there was a contusion and bruising on her left forearm, along with multiple pains reported in different areas of her body. These injuries appear to have been caused by a blunt, edged instrument, such as a candlestick, a key, or something similar. To prevent dangerous complications such as fever or abscesses, I prescribed strict rest, confinement to bed, and medical treatment twice daily. If no complications arise, the wound should heal within fifteen days. This I certify as true. Given in Paris, the 7th of this month and year above.”

(Signed) Desportes(3)

Despite its lack of proper spelling, this certificate attests to the danger of facing Mademoiselle Maupin’s wrath. However, the matter had no serious consequences for the actress, whose defense we do not have. She must have found a way to exonerate herself, or perhaps the authorities turned a blind eye. As we would say today, the case was dismissed.

(1) This document is the only evidence we have that Mademoiselle Maupin had a sister; no other sources mention her. Given the singer’s reputation, it is possible that she passed off a woman she lived with as a relative.

(2) National Archives. — Papers of the Commissioners y 15561. File as of Sept. 6, 1700.

(3) National Archives.–Papers of the Commissioners y 15561

From La Maupin (1670–1707), Sa Vie, Ses Duels, Ses Aventures by Gabriel Letainturier-Fradin, Chapter XI, “Chez le Commissaire”, pp. 147–155.

Original French translated by ChatGPT.